UM wildlife biology grad is revealing the fate of the frozen frontier

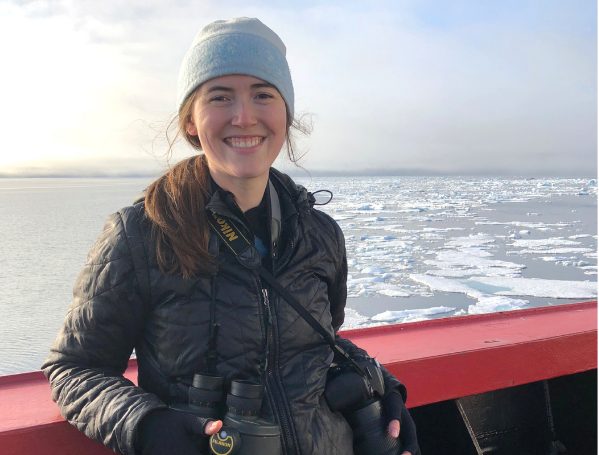

UM wildlife biology alumna Jessica Lindsay '15 recording audio in the Seeley Valley for a project as an undergrad. She has worked as a researcher for the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration’s Polar Ecosystems Program since October 2023.

On the thin ice of rapidly warming Northern Alaska, Jessica Lindsay has been conducting research that helps to unveil how a warming planet is diminishing the habitat for arctic native species.

Lindsay graduated with a bachelor's degree from the wildlife biology program at UM in 2015. She has been fascinated with animals ever since she was a kid, but it was when she came to Montana that a real interest in finding the intersection between the impacts of climate change and wildlife sparked.

“Montana is a place where there is so much opportunity to work with wildlife, and while attending UM I got so much experience,” Lindsay said.

She has worked a variety of jobs in the field— from conducting research for a raptor project in Missoula to studying the evolution of guppies in Trinidad and Tobago. According to her longtime mentor and UM wildlife biology emeritus professor, Erick Greene, Lindsay showed an aptitude for approaching science creatively.

“Jessie was always a very impressive student,” Greene said. “Even her work in undergrad was graduate level. She has a keen sense of creativity that allows her to take really complicated data and make it crystal clear.”

Lindsay recently completed her Ph.D. studying sea ice change and ringed seals in Kotzebue, Alaska, for the University of Washington. She was hired at the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) before even completing her degree. Lindsay’s research helps gain new insights into how a changing climate is quickly reducing the habitat of marine mammals in the Arctic.

While conducting her six week-long field work, Lindsay described her typical day as a ride onto the sea ice via snowmobile with one or more Indigenous Iñupiaq Elders from Kotzebue. According to Lindsay, ringed seal snow dens are found over a hole in the ice where seals have burrowed out to breathe. She and the Elders would look for ringed seal dens and breathing holes to try and understand how behavior patterns were changing based on the species’ history in the area.

The Elders advised Lindsay on this history of the ringed seals and their denning patterns from their community perspective of living alongside them for centuries — informing her where breathing holes and dens have been in the past and explaining the variations caused by a changing environment.

The Elders advised Lindsay on this history of the ringed seals and their denning patterns from their community perspective of living alongside them for centuries — informing her where breathing holes and dens have been in the past and explaining the variations caused by a changing environment.

“I really valued the work I did with the Elders,” Lindsay said. “Without their insights, we wouldn’t have been able to check whether our models were working. That knowledge is really important.”

Lindsay said the Iñupiaq Elders were fundamental in informing the overall design of the Ikaaġvik Sikukun (Iñupiaq for “Ice Bridges”) study, which also included team members from Columbia University, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, NOAA, and Farthest North Films. The Elders’ familiarity with the seal populations provided a unique perspective on the data and for her, an outsider coming into a new ecosystem, helped to translate a nuanced understanding of the environment. The Iñupiaq Elders were all co-authors on the research papers from the project — something not typically seen in published Western science.

When it wasn’t safe to go out onto the ice to collect data, Lindsay and team members would deploy drones that used infrared sensors to track where the seals were. Further insight from the Elders helped to fill in the information gaps. The overall dataset looked at the snow and sea ice topography, water depth, and survey date in relation to the presence of ringed seals.

Lindsay received further context when she was given the opportunity to go out on a three-week excursion with the Coast Guard aboard the Healy, the United States' largest and most technologically advanced icebreaker. It is also the US Coast Guard's largest boat and in 2015 became the first unaccompanied U.S. surface vessel to reach the North Pole.

“You do a lot of number crunching in wildlife biology,” said Lindsay. “I think it's really important to go out into the ecosystem you’re trying to understand to gain further context.”

Since October 2023, Lindsay has officially been a part of NOAA as a researcher in their Polar Ecosystems Program. She says that the research she did in her Ph.D. helped to prime the pipeline for her work with NOAA, and she plans to continue her work studying the Arctic and the impacts that climate change is having on wildlife in this vulnerable region.

According to Greene, Lindsay’s work is extremely important for making connections on how changes with a species can inform changes in the environment.

According to Greene, Lindsay’s work is extremely important for making connections on how changes with a species can inform changes in the environment.

“Jessie’s research on ringed seals is shedding light on why this keystone species struggles with climate change,” he said. “It will help to comprehend the consequences that might result on ecological communities and interactions within the Arctic.”

“Climate change presents some pretty extreme challenges for the Arctic,” Lindsay said. “I hope to continue to learn more information on the timing and severity of these impacts on marine mammals to further our understanding.”